New Music, Old Music: June 2025

Planning for Burial, Stereolab, Sleigh Bells, Lil Wayne...

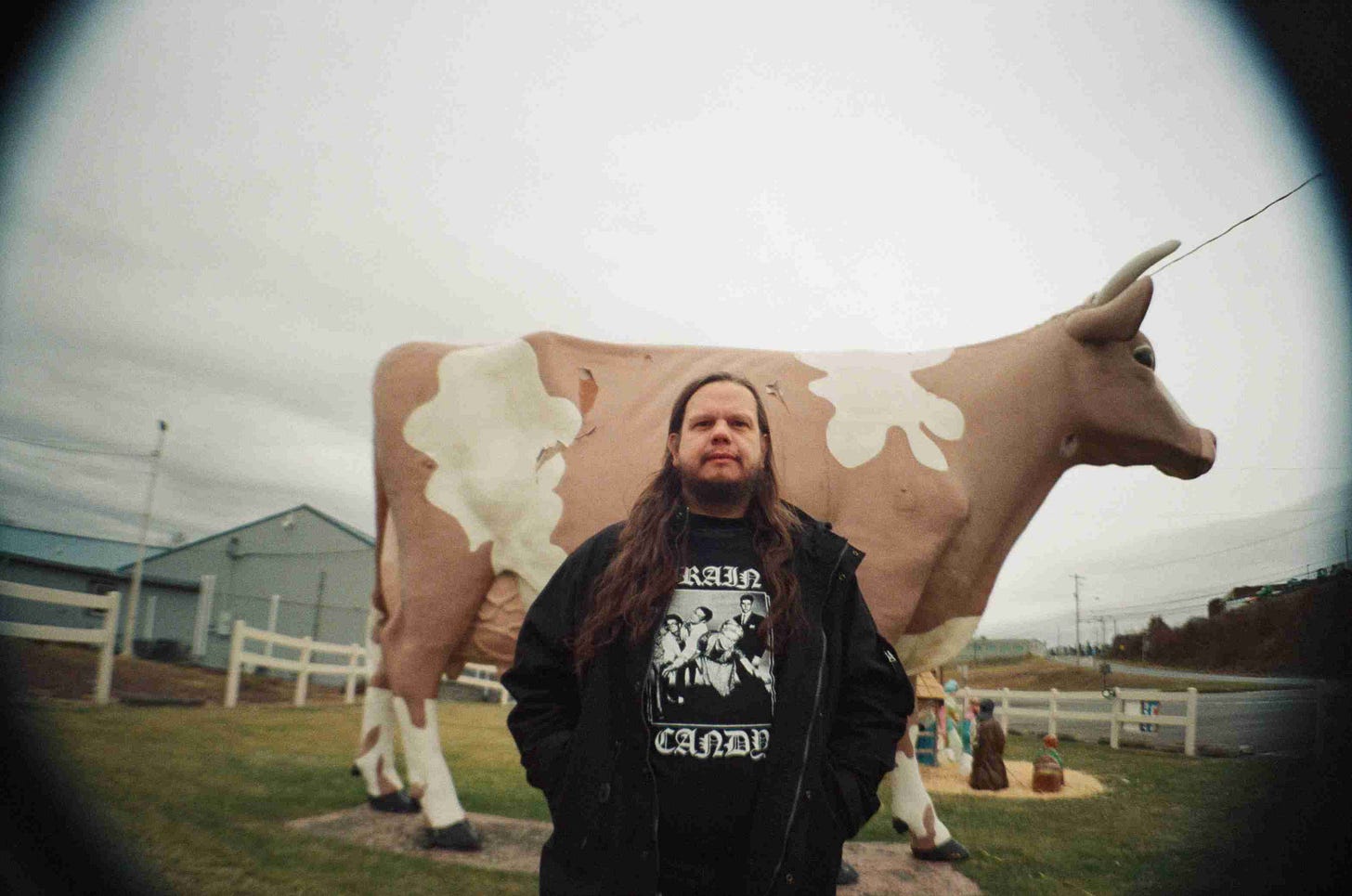

It’s Closeness, It’s Easy

The new Planning for Burial album “It’s Closeness, It’s Easy” will be one of the best rock albums this year, one of the most interesting, anyways. The band, a solo act of Pennsylvanian Thom Wasluck, fits neatly into a surprisingly definable nexus of genres, blending shoegaze with metal-core, screamo—alá Deafheaven—but with a heavy punch in the guitars, an immediacy to the melodies and vocals, that could suit tastes from the Deftones to Citizen. And, a studied use of noise and drone—all those twisting tones winding into the beyond—that raise dread hackles and could remind of Prurient; ghostly, shiny splinters of sound like those of Godspeed You! Black Emperor.

This vague common ground genre, that is both heavy and atmospheric, full of dread and full of light, earthly yet hovering, all at once, is a fertile and well-trodden ground for the current generations of underground or independent rock music. From Title Fight to julie, and, broadening the intersection of genres even more, Yves Tumor and spirit of the beehive. Rock music is rapidly growing and splitting under the surface like a healthy body of cells. In this context Planning for Burial’s experimentation is far from singular (experimentation is almost expected outside the mainstream), but the execution of this album’s sound, ranging from spine sizzling drone to mind-crushing crunch, is exceptional.

“It’s Closeness, It’s Easy” is one of the most satisfyingly dynamic albums I’ve heard in a long time. Dynamism can itself become a flat buzzword circling music talk, as it gets endlessly repeated along the factory line from audio engineers to critics to your friend’s older brother; but used simply to describe the application of a full range of different effects, loudness, level of violence, pace or rhythm, it aptly describes this album. The range of guitar tones alone, is awesome. Jangly acoustic strums to harmonic plucks to bone shattering bursts and heavy dirges, all played through a variety of effects, some beautiful, some jagged. And the range of the playing, too, is effective. The first track, “You Think,” opens with rapid, slamming mayhem timed to double-pump metalcore kick drums, but the track ends with soaring metallic resonants played with a steady, funereal hand. All along the way the speed and style of the playing goes linked, pick and pedal, toward achieving the desired effect. In the epic heaven bound chorus of “You Think” the pattern actually speeds up, though the drums slow, the guitars shifting further back in the mix, taking on a ringing, hollow quality, as if played from the far end of a tunnel, and the space those additional chords fill takes over for the slumbering rattle of the drums. On track seven, “Twenty-Seventh of February,” the guitar is played in a hypnotic sludgy pattern, closer to something by Sleep, yet its tone has become fuller, crunchier, rolling, and so becomes a wall of sound. This attention to the playing and recording of the guitars is nothing new, but it’s so exceptionally effective on this record—like a painter using brush strokes and color values masterfully.

Guitars and drums may be the most obvious instruments across many of the tracks, but their dynamic contributions are often just the bedrock. For such a heavy album “It’s Closeness, It’s Easy” uses an amazing assortment of little sounds—bells, chimes, whispers. Graceful twinkling piano keys opening doors to harmonic ambient passages. The dynamic range of the recording makes us want to lean in, even while being pummelled. And the attention to the mix is so acute that we can hear all of these elements, not evenly, but fully—again, like a painting with a great use of composition. A sharp, buzzy guitar lead might wiggle its way forward, like in track eight, “Fresh Flowers For All Time,” but not at the expense of the ragged, choked vocals—in fact, these guitars carry the vocals up with them, ascending the mix in long strides as the chorus arrives.

The vocal range, too, is dynamic. Not just dynamic, but genre spanning. The whispering is dramatic, emotive; shouts rise to yells, slotting in behind driving, heavy shoegaze guitars, and the unpolished, shredded quality of the vocals, in every register, derives a certain performative drama that can shift a track from death-metal to emo to post-rock. Plaintive yelps, impassioned crescendos and brimming hums, the occasional sing-talking reminiscent of Slint’s “Spiderland”—Wasluck’s vocal delivery is a major element of this album’s success.

I was enamored by an earlier Planning for Burial album, 2017’s “Below The House,” especially track four, “Warmth of You,” which wildly (and sweetly) blends The Cure and early my bloody valentine into something both sharp and gauzy. “It’s Closeness, It’s Easy” has all the obvious marks of a creative (and technical) step forward. A grander, more nuanced production style, influences rendered in original, genre-bending ways, and fantastic playing and performance. Simply, it kicks ass. The tracks on “It’s Closeness, It’s Easy” will pummel you, get stuck in your head, and may cause eager, mellow dissociation.

Instant Holograms on Metal Film

The new Stereolab album opens with a pinging synth arpeggio that could’ve been tucked into a Playboi Carti or Ken Carson beat, which may give false hope that the band knows it’s making music in 2025, and yet the following songs soon settle into a sound easily categorized alongside the bands early classic records.

“Aerial Troubles,” track two, builds out of this brief arpeggio prelude, and then returns to it. The track features elements familiar to Stereolab listeners. A driving, pulsing rhythm and a bed of sparking, jangly guitars, swirling synth pads, plunking bass, layers of breathy, sensuous vocals. Despite the recognizable, there is something fresh and novel about discovering these unfamiliar Stereolab songs in 2025. Perhaps nothing more novel then the uncanniness of the band sounding almost the same now as on “Dots and Loops” or “Emperor Tomato Ketchup.” The mix is cleaner, digital, sparkling, but the compositions are eerily similar.

“Melodie is a Wound” swings through a linear progression of funky, quippy, space-age electronic music filled with the motifs and attitudes of indie-rock—Stereolab’s patent sound. Even the deviations are expected, the sonic freak-out near the close of the song, or the splitting textures signaling changes of pace.

The formula is recognizably productive. For fans of Stereolab, “Instant Holograms on Metal Film” won’t be about nostalgia as much as about the band maintaining a semblance of quality. For new fans, it’s as good a place to start as any.

The flow of the album is wonderful. The tracklist pulls us through a variation of moods, the beginnings and endings of songs often feeling like radical mood shifts, while the twisting tones at the center of these compositions sometimes match up, giving the album a cohesive, upbeat though melancholic vibe.

“Immortal Hands” features a drum and synth breakdown that hints at the band’s ear for experimentation. The insertion of other rhythms, whether it be classic hip-hop breaks or dance music four-on-the-floor, is an interesting sonic ripple for a band whose krautrock influenced, metronomic bustle is accounted for. “Electrified Teenybop!” goes farther, possibly answering the question of what a band like Stereolab might sound like in a world post-EDC. Rising rave synths poke around behind the thumping, distorted drums. The appearance of this blended aesthetic in their music makes Stereolab sound more like a cross between Kraftwork and Air, rather than the progenitor of a sound themselves. Their consistency belies their innovations. The aesthetic creases and permutations on this album are too few to be a reinvention, and are interesting enough suggestions to beg for more.

Loud, Harsh, Sweet

Around the time I first listened to “Treats” by Sleigh Bells, I was also listening to “Psychocandy” by The Jesus and Mary Chain, and taking a commuter train through snowy North-of-Boston suburbs, changing to a bus at Harvard Yard, making my way to an office in Allston to work on transcriptions for a documentary company. The mood was comprehensive—iced in Massachusetts drear, internship drudgery, spazzed out noise rock—and I was transcribing interviews about the Boston strangler, naturally. The catch with both artists, the rub, is that a certain sweetness undercuts their cruelty (cruelty towards instruments, compressors, levels). I remember “Treats” being on loop, the hooks and riffs so melodic they’d stick in my head, always craving another hit. Not only does Sleigh Bells incorporate an affinity for harmony (and dissonance) that calls back to The Beach Boys or The Ronettes, but their raw, thick sound is just the obvious next step for Phil Spector’s “wall of sound” pop-music.

“Psychocandy” was a kind of reprieve from the saccarchine blood-rush of “Treats.” After hours of manic transcription the slow, bumpy train ride home, with views of snowy lots and darkened malls, was accompanied by those sizzling harsh chords, ringing hollow in a mix so sparse that it fit the dead landscape. The Jesus and Mary Chain also appealed to me because they seemed to be intensifying, obscuring, an older, more innocent kind of music. Like Suicide, another one of my favorite bands, they twisted the sounds of ‘50s and early ‘60s rock into darkly textured echoes. I was realizing two things around this time, that pastiche could be original, and that deafening noise quieted my percolating mind.

Despite the long days and summer heat I’ve been finding myself seeking loud, dark music. Aggressive, delirious, occasionally inconsiderate of hearing. Very frequently I’m looking for moods and feelings fit neatly into albums, rather than single tracks that I might fit into a playlist (I struggle to focus on playlists long enough). A search that led me back to Crystal Castles and Salem’s “King Night,” both of which find specific moods within a stream of dark harshness, sappy sweetness, and various genre rip-offs. Crystal Castles’ debut can make me dance, and be scared, at the same time. Here, again, the melodies are like demonic, robotic interpolations of early-2000s dance hits. There’s a sweetness tucked in alongside the distorted kicks and off-key synths.

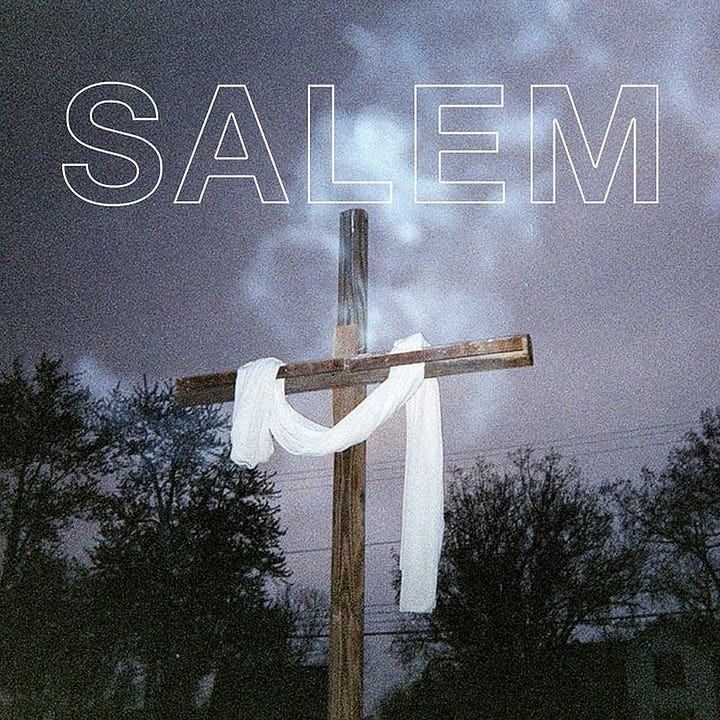

Salem’s “King Night” is, I think, one of the greatest ‘vibe’ albums ever made. For one thing it captures, sonically, whatever is going on in the album cover—a deep, perverse, neo-Americana mysticism with roots in Three-Six-Mafia rather than Appalachian banjo music, but deeply, perversely, American all the same. In many ways it might be the most distinctly American album of the twenty-first century, though I’m not entirely sure why I’m saying that.

What I do know is that the crunchy bass hits of “Asia” makes me think of Sleigh Bells’ “Tell ‘Em,” and the wispy synth that rises from the murky depths of that track, gliding like firebirds from hell, beautiful and tragic, haunts me in a similar way to the creepy high-pitched snarls of the Sleigh Bells song.

Peanuts 2 N Elephant

Unironically, I feel that Lil Wayne’s new viral song “Peanuts 2 N Elephant,” which is leaving fans, content creators, FL studio producers, and passersby flabbergasted, is pretty good. I take no issue with the assertion that Wayne’s new album “Tha Carter VI” is pulling punches, landing nowhere close to earlier albums (even “The Carter V,” which I liked), and maybe I am just being stubbornly contrarian—I just think the zaniness of the beat is being underappreciated. All of the hate is indeed being directed toward the beat, which is—bizarrely—produced by Lil Manuel Miranda, and has incited numerous videos of producers demonstrating how stupidly simple it is. Well, who cares about that? Simplicity isn’t the issue, really, more that it sounds like Donkey Kong club music. But considering the title, the actual elephant sounds and references, I’m sure that’s intentional. The video below, intended to dunk on the production, I think actually shows what I find so interesting about the beat. It’s made almost exclusively of discordant preset sequences that interlock in off-kilter ways, giving the beat its goofy rhythm.

Maybe it is the worst beat ever made. Wayne has certainly rapped over better, more lush and expensive, beats. And yeah, only someone like Lin Manuel Miranda is getting this beat placed on a major release. Maybe I like it for the same reason I like Yuno Miles, I like weird. When something is so off-base that the majority turn their backs, I like to raise my voice and say, “that’s avant-garde.” Maybe it’s teasing, or trolling, or maybe I’m right. Either way, it’s not a bit. I’ve been listening to “Peanuts 2 N Elephant,” I actually like it.